States, Actions, Rewards - The Intuition behind Reinforcement Learning

In 2014, Google acquired a British startup named DeepMind for half a billion dollars. A steep price, but the investment seems to have paid off many times over just from the publicity that DeepMind generates. ML researchers know DeepMind for its frequent breakthroughs in the field of deep reinforcement learning. But the company has also captured the attention of the general public, particularly due its successes in building an algorithm to play the game of Go. Considering the frequency with which DeepMind makes progress in the field - AlphaGo, AlphaGo Zero and AlphaZero in the last couple of years - it becomes hard to keep track of what exactly is happening, both at a technical level and from the point of view of implications. I plan to do just that - provide a high-level view of DeepMind’s successes in Go, and explain the distinctions between the different versions of AlphaGo that they have produced.

But first, for context, I’d like to give a overview of reinforcement learning (RL) in general, and that is what the rest of this particular post is dedicated to. I’ll try to keep things intuitive, and point to more detailed technical resources if you’re interested in learning more. One excellent resource that gives a good technical overview of RL is this post (yes, I’m a big fan of Andrej Karpathy’s blog, definitely check it out!)

What is RL?

Machine learning is a field that is ripe with comparisons to human cognition. This is not a coincidence of course. Many of the most popular tasks in the field (vision, speech and natural language processing) have typically been the domain of human (or natural) intelligence. As “what” the algorithm is doing is emulating humans, it is natural to think of “how” the algorithm works as emulating humans as well. Hence the abundance of statements like “Neural networks are inspired by the human brain” (In truth, that statement is only as true as “Aeroplanes are inspired by birds”)

Reinforcement learning is particularly opportune for such comparisons. At its core, any reinforcement learning task is defined by three things - states, actions and rewards. States are a representation of the current world or environment of the task. Actions are something an RL agent can do to change these states. And rewards are the utility the agent receives for performing the “right” actions. So the states tell the agent what situation it is in currently, and the rewards signal the states that it should be aspiring towards. The aim, then, is to learn a “policy”, something which tells you which action to take from each state so as to try and maximize reward. This broad definition can be used to fit a number of diverse tasks that we perform everyday.

When you drive, the state is the position and speed of your car and the neighbouring cars. The actions you can take are turning the steering wheel and pressing the accelerator or brake. The reward is dependant on how quickly you reach your destination while respecting traffic rules. For example, this is how a self-driving car may see the state:

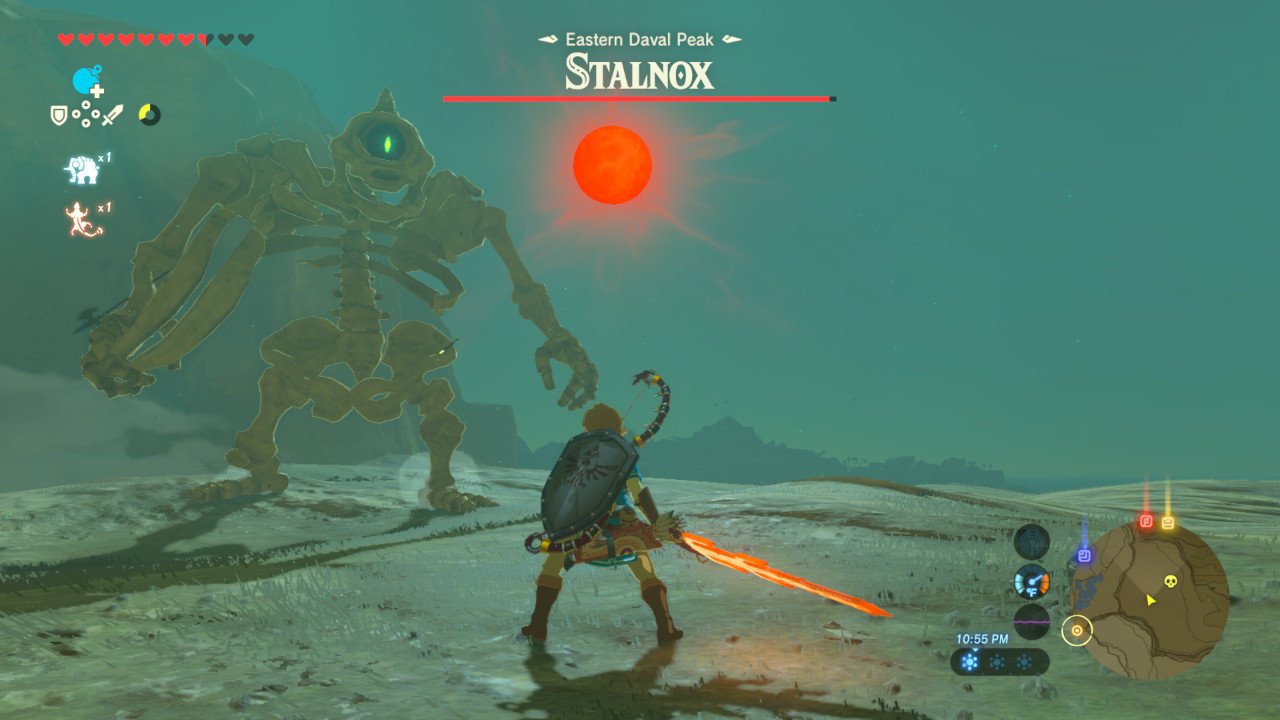

When you play a video game (say, The Legend of Zelda), the state is whatever information you have on the screen - your location, the presence of nearby characters or monsters, the weapons and items you possess. Your actions can involve moving or attacking. Your reward depends on the number of lives you have remaining and any money or items you gain from defeating an enemy.

Let’s look at a more abstract example - applying for grad school. Your state is your current research/work profile, and the information you have about programmes and professors at different schools. Your actions may be deciding who to ask for a letter of recommendation, what to put on your SoP, and which schools to apply to. The reward, of course, is an acceptance letter (or a negative reward due to a rejection letter).

These examples show that it is often possible to frame myriad tasks at different levels of “concreteness” in terms of a reinforcement learning setup. However, it is important to note that the scope of the state, action and reward set may be very different for different tasks. For instance, the action set in a Zelda game, while extensive, is clearly an order of magnitude smaller than the action set for applying to grad school. This suggests that framing tasks as reinforcement learning works well when you have clearly defined states and rewards and restricted action sets. This can be seen in the types of tasks that RL has shown success on.

Solving RL Tasks

One common approach to solving RL tasks is called “value-based”. We try to assign a number to each state (or each (state, next action) pair ) based on which states are likely to lead to high rewards. This entity connecting each state to a particular numerical value is called a value function. If we learn an appropriate value function in this way, then from a particular state, we can simply choose the action that is likely to lead to a next state with a high value. So we’ve now reduced our task to the problem of learning this value function.

To understand what this learning process may look like, let’s look at a more concrete example - tic tac toe. The state is the current board position, the actions are the different places in which you can place an ‘X’ or ‘O’, and the reward is +1 or -1 depending on whether you win or lose the game. The “state space” is the total number of possible states in a particular RL setup. Tic tac toe has a small enough state space (one reasonable estimate being 593) that we can actual remember a value for each individual state, using a table. This is called a tabular method for this reason. This isn’t practical in most applications (imagine listing out all possible configurations of a chess board and assigning a value to each one), but I’ll come back to how to deal with that later.

We start by assigning some initial values to each state, say 0 for all states (there are better initialization strategies, but this will do for now). So initially, our table looks like this (let’s say we have some way of numbering or indexing the states):

| State Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| ... | 0 |

| ... | 0 |

| 593 | 0 |

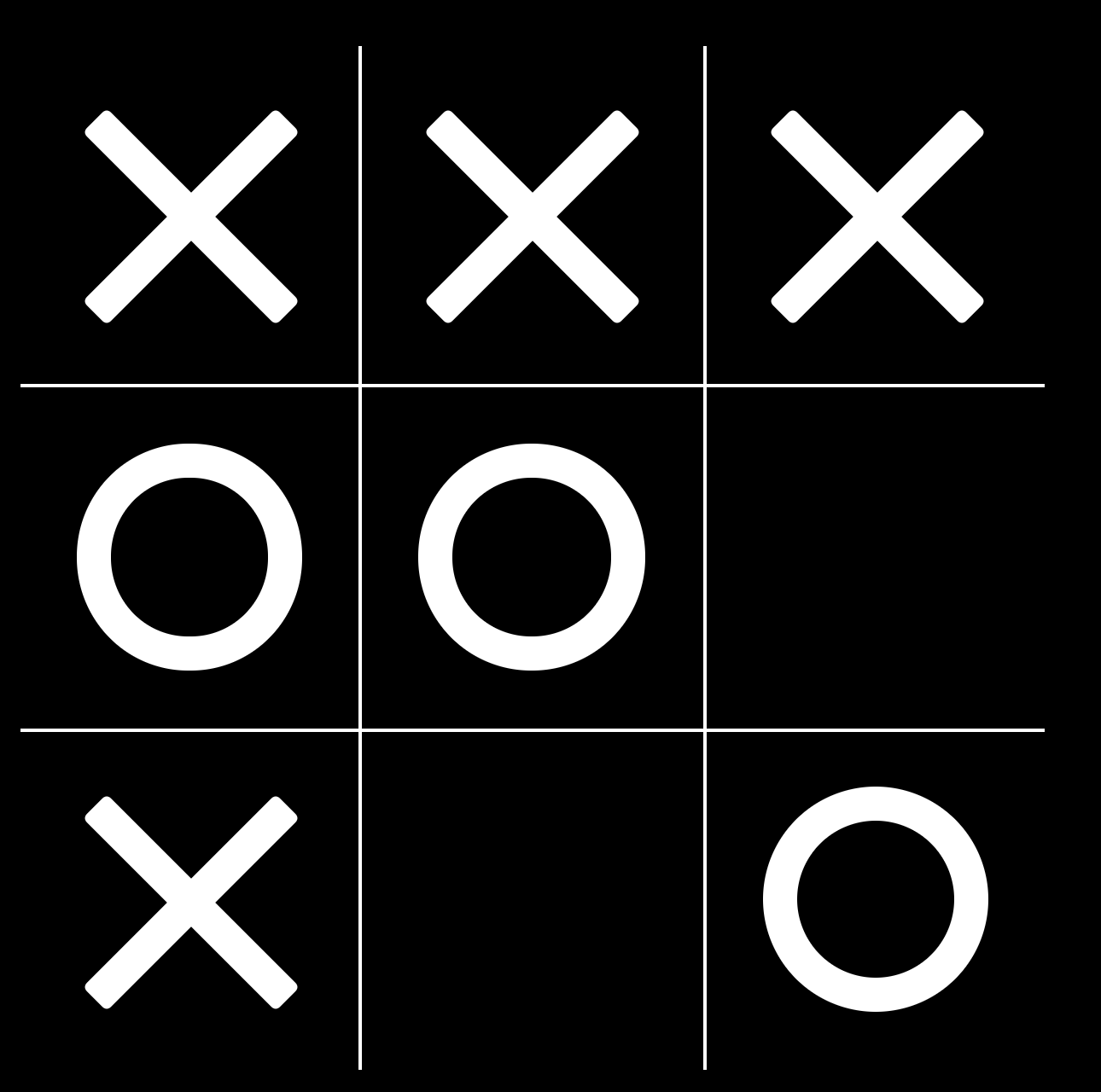

We then start playing games of tic tac toe against an opponent, where we follow the general rule that the action taken in the current state is the one that leads to a next state with as high a value as possible. In the beginning, as all states have equal values, this would mean just picking randomly from the set of legal moves. But after a few games, you notice that when you reach this position (you being ‘X’):

You get a reward of +1. The value associated with that final state must be +1 then. So you update your table (say the final winning position has an arbitrary index of 123):

| State Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| ... | 0 |

| 123 | 1 |

| ... | 0 |

| 593 | 0 |

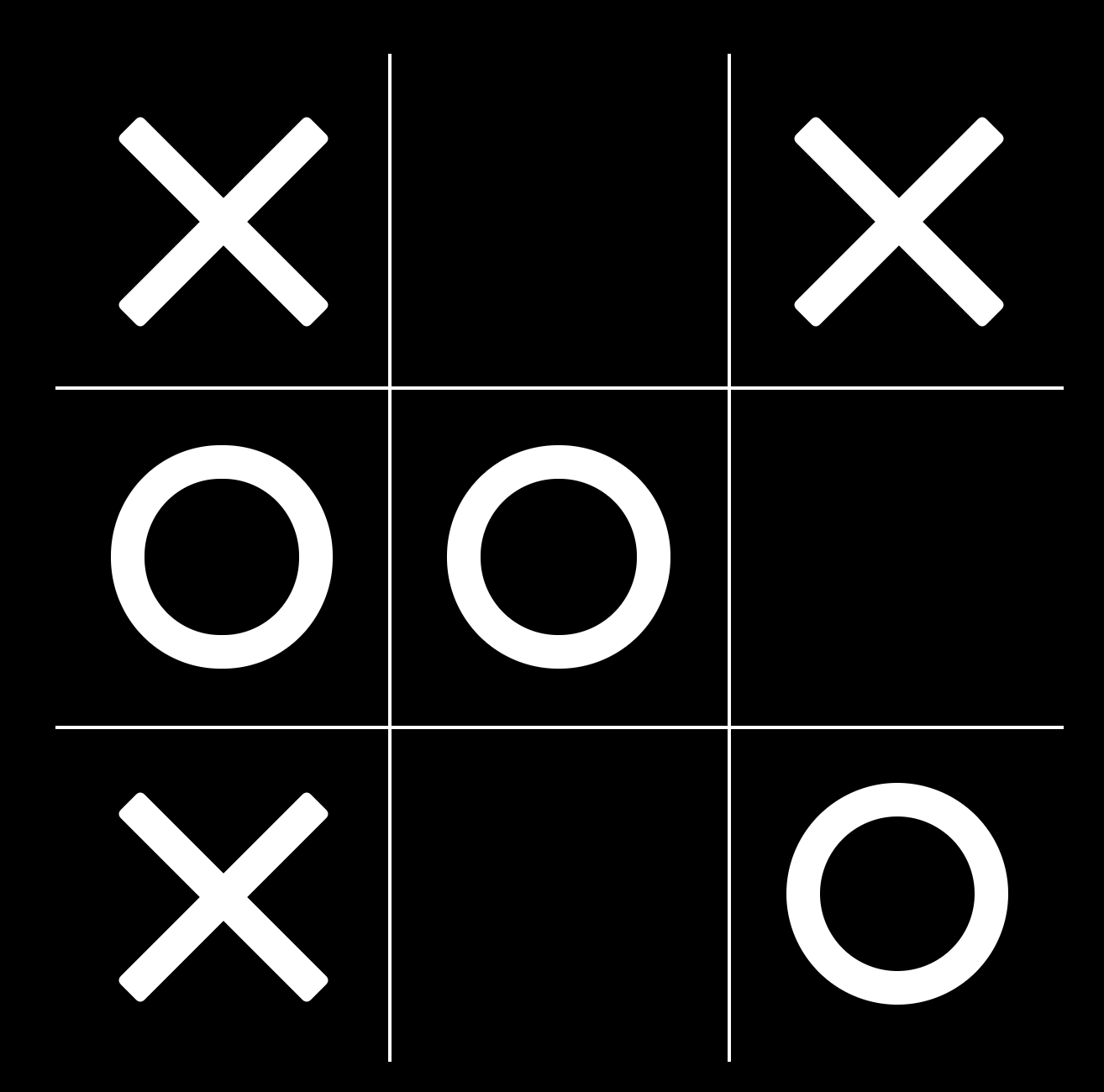

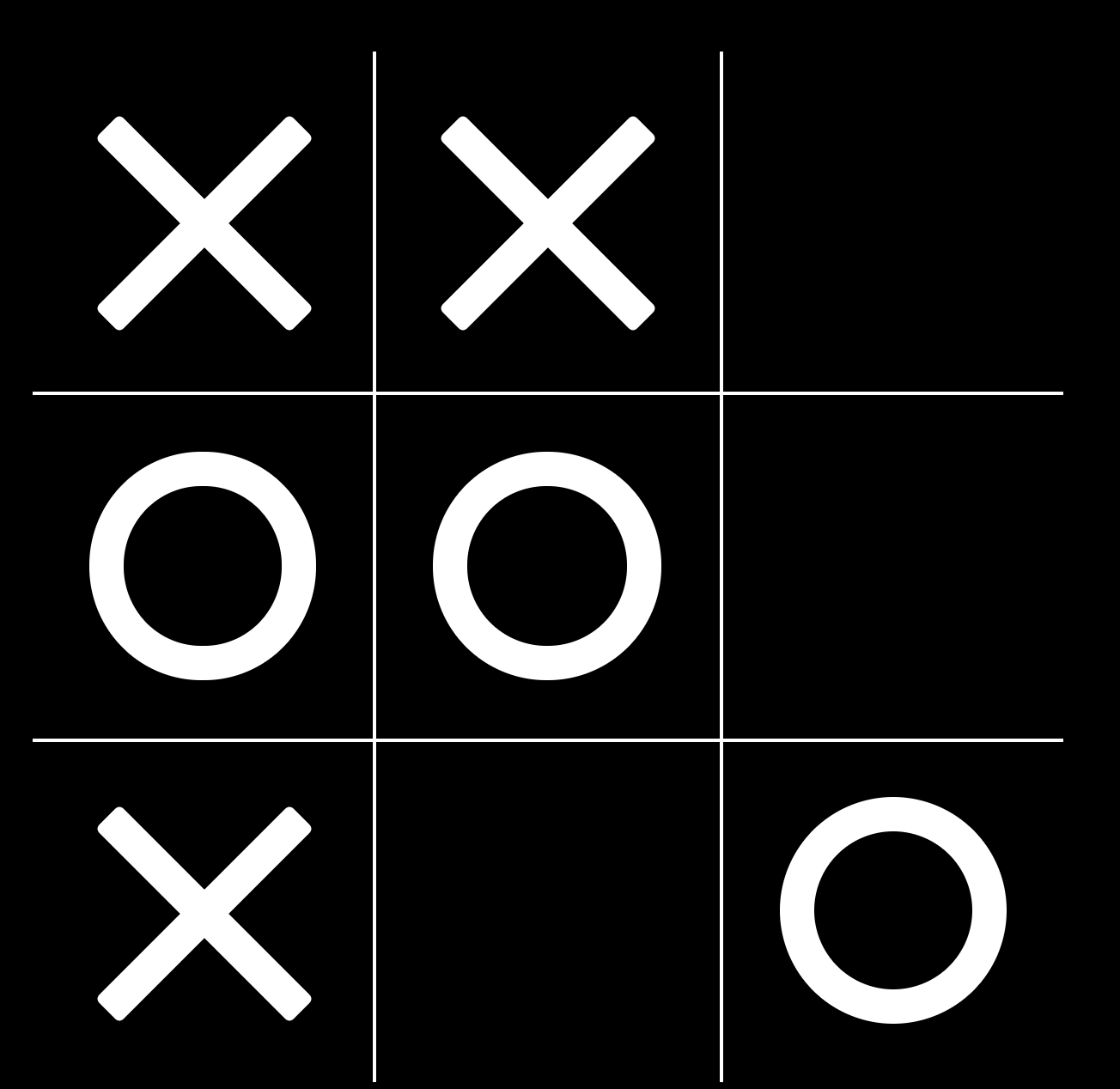

Now, in the next few games, you see that the positions that you lead you to 123 (let’s say these are 121 and 122 respectively) are also likely to end with a high reward, as long as you play the right move:

So you update the table again, noting that this penultimate state doesn’t necessarily have the full reward of +1, as it is still possible to make the wrong move and end up with a loss or draw:

| State Index | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| ... | 0 |

| 121 | 0.9 |

| 122 | 0.9 |

| 123 | 1 |

| ... | 0 |

| 593 | 0 |

I won’t go into the actual equations involved, but at a high-level we see that the reward is sort of “flowing” backwards from the final (terminal) state, and giving a concrete value to the states that lead up to it. These terminal states are thus extremely important in ensuring that the algorithm learns the right value function. I once had a bug where everything was working as expected except the flag indicating these terminal states, and the algorithm ended up learning almost nothing.

So, given enough training games, the reward will flow all the way back to the very first states, and you have a good strategy from beginning to finish! For instance, one common way to do this “bootstrapping”, where the value of one state is learnt from the value of the states that come immediately after it, is called Temporal Difference learning.

Extending to Chess

How well does this strategy work for, say, chess? Tic tac toe has around 600 states. While it is difficult to calculate the exact number of states in chess, a good upper bound seems to be 10^45.There isn’t enough memory in all of the computers in the world to store that many states, so putting all the values in a table isn’t a good idea anymore. How do we handle this issue?

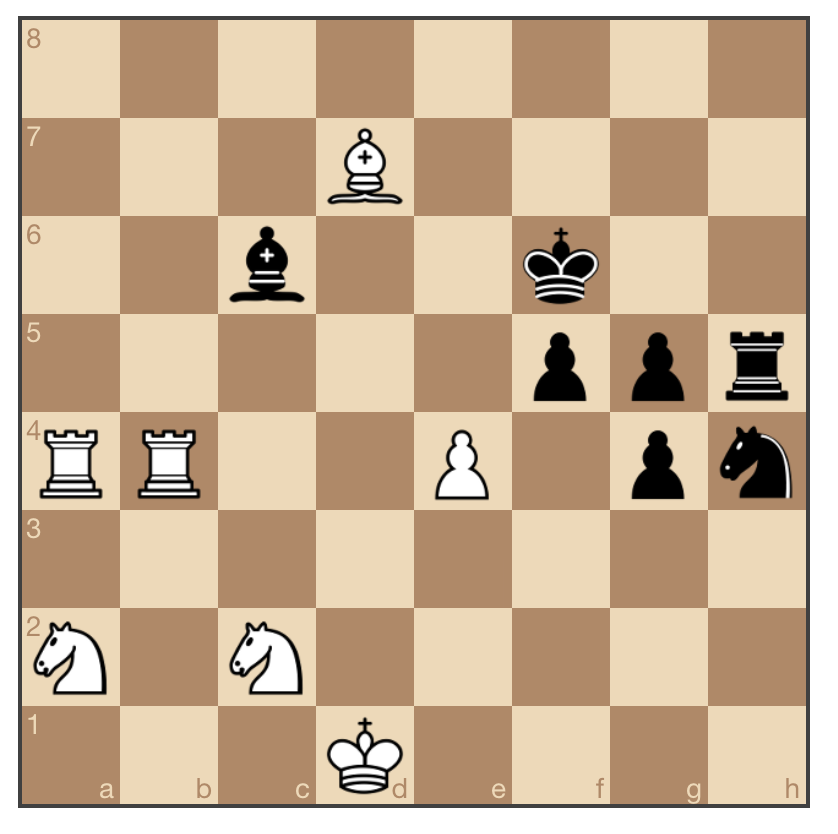

Let’s think about we play chess. As we practice more, we start getting an intuitive understanding of how “good” certain states are. For instance, try to evaluate this state (white to play):

You can probably tell that white has the better position. It’s likely that you’ve never seen this exact board state before in your life. Nevertheless, you’ve built intuition about what constitutes “goodness” of a state in chess. You probably counted the number of pieces that each side has left, and noted that while black has 2 extra pawns, white has an extra knight and rook, giving that side the advantage. If you’re a more experienced player, you might have looked at possible next moves (white bishop could take the black bishop for instance) and the sections of the board that each side controls.

So you’re definitely not memorizing the potential value of each possible chess position - you’ve learnt some kind of a general function, mapping the state of the board to the value of the game for each player. This is exactly what we would want a smart chess algorithm for RL to do as well, through an idea called value function approximation.

First, we figure out a way to represent the game state. For tic-tac-toe, we could just enumerate all the states, meaning that each game state was represented by a single number. For chess, one simple way of doing this would be to represent each piece with a number (pawn → 1, rook → 2 …) and then have a list of length 64 that encodes the presence of a particular piece on each position (with, say, 0 for the empty positions). We could feed this into the value function that our RL algorithm has learnt, and it would spit out a number (representing “value”) or maybe a probability (representing the chance that black wins).

Now the actual RL part is very similar to what we did for tic-tac-toe. We play lots of games, reward the algorithm for winning and penalize it for losing, and over time it will (hopefully) learn a good function representing the value of a state. The only change is that in place of looking up a value from a table, we pass an input through our function and get the corresponding value as output. Having this, we can derive a policy to play chess by looking at what state we’d reach by taking each possible legal move, and pass each of these states through our function to see which one has the highest value!

This was a fairly naive way of approaching the chess problem with RL, and there are some sophisticated ideas we can use to speed up computation, improve learning and eventually make better moves. This is going to be particularly important in the case of Go, where the state space for the game is even larger than for chess! This was all probably a lot to take in, so I’ll stop here and discuss some of these interesting ideas in the context of Go in the next blog post. Thanks for reading!