The Technology and Promise of AlphaGo

In the previous post, I gave an intuitive view of the workings of reinforcement learning, and worked through how the learning process would play out for tic tac toe and chess. Now, let’s get to the really interesting stuff - Go!

Go is a Chinese board game that’s been around for millennia. The rules themselves are fairly straightforward, much simpler than chess. Players take turns putting black and white pieces on a 19x19 grid, and the one who manages to surround the most territory wins. But while the game is easy to pick up, it is notoriously difficult to master due to the long-term strategy required to play at a high level of expertise.

Part of the reason that it has captured the attention of the machine learning community is the astounding size of its state space. Remember when we saw that the state space for chess is about 10^45 in size? Well Go is closer to 10^170. Our minds aren’t really capable of grasping how large a number this is, but at this sort of scale, any issues we might have in exploring the state space of chess are even worse in Go. DeepBlue’s defeat of Garry Kasparov in 1997 involved a lot of hand-engineered human features and exploration of a decent chunk of the chess search space using massive computational power. Extending that sort of approach to Go would be impossible. Playing the game requires a certain creativity and intuition that computers were thought to be incapable of, and this is why it was widely believed in the ML community just a few years ago that reaching human level performance in Go would take a decade or more.

Enter DeepMind and AlphaGo.

After working on AlphaGo for close to 2 years, in October 2015 DeepMind played Fan Hui, the reigning European Go champion, and beat him 5-0. This was the first time a Go AI beat a professional human player without handicaps. Just a few months later AlphaGo did something even more unexpected - it beat Lee Sedol, one of the best Go players in the world, in a highly publicized event in Seoul, 4-1. This was the moment that catapulted Deep RL (and DeepMind in particular) to the forefront of the public discourse on AI. If you’re interested in the specifics of the Fan Hui and Lee Sedol matches, I highly recommend this documentary.

So, how exactly does AlphaGo work?

The Ideas behind AlphaGo

Once again, to gain an intuition of how AlphaGo works, let’s think about how we as humans approach a complex strategy game like Chess or Go. The way I see it, there are 3 vital aspects to our game-playing behaviour:

- Forward Simulations - You often hear people say that professional chess players think many steps ahead before deciding on their current move. This ability to scan through possible future opponent moves and board positions to decide on the next move is important to playing the game at a professional level.

- Estimating value - Like I mentioned in the previous post, it is possible for us to just look at a board position and get an idea of how probable either side’s victory is from it. This is also important for running simulations. Ideally, we would want to think ahead all the way to the end of the game, but that is clearly beyond the ability of even the best professionals. So instead, we think ahead 5 or 10 steps, and evaluate the “goodness” of the board position that we end up with.

- Promising moves - At any stage in the game, we do not necessarily go over every possible legal move that we could make. Especially after sufficient practice, the promising moves come to mind without you even thinking about them. This is helpful for your ability to think ahead as well, because if you can prune away unlikely moves at each stage, your “simulations” can go farther ahead.

Most Go engines before AlphaGo achieved the first of these, forward simulations, using an idea called Monte Carlo Tree Search. Sounds fancy, but the basic idea is exactly what you would think of when you imagine simulating a game - the algorithm guesses the moves that each player would make in the future, and examines where the game ends up (who wins). First however, let’s focus on what AlphaGo managed to achieve that other algorithms before it did not - coming up with promising moves, and estimating the value of a board position, using a “policy network” and a “value network” respectively.

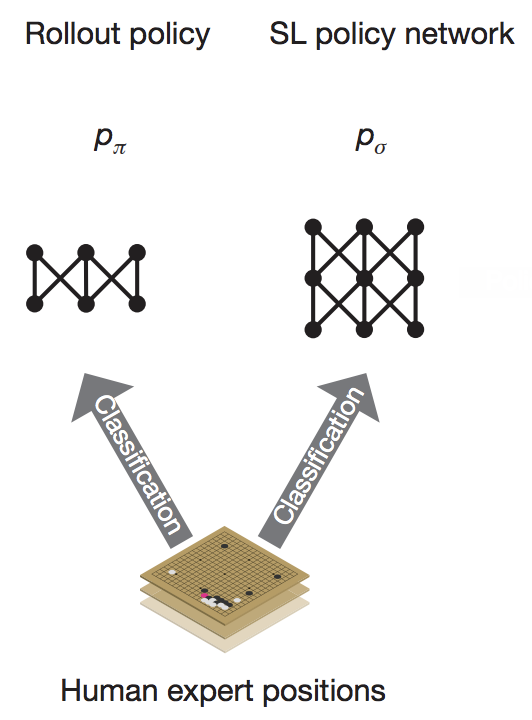

The policy network was trained in two stages. Stage 1 is a type of machine learning called supervised learning. The team took an immense amount of data from professional Go matches, and trained the algorithm to predict what moves a human player would make from a given board position. They trained two versions of this network, with one essentially being much smaller than the other. The smaller network took less computation to run, but as a clear trade-off it was less accurate in predicting the correct human move. This smaller network is called the “rollout policy”, and I’ll come to how it’s used a little later. The other one is the SL (supervised learning) policy network:

Stage 1 of training is “supervised” as we explicitly tell the model what the correct answer (move) is for a given input (board position). But there is one obvious limitation with this - what makes the human player’s move “correct”? In theory, this could get AlphaGo up to the level of a professional human player, but no further.

That’s where Stage 2 of policy network training comes in - reinforcement learning. With the result of the previous stage of training as a starting point, AlphaGo was now retrained in a manner similar to the tic-tac-toe and chess examples from the previous post. It played against itself many many times, and it encouraged moves that led to a win and discouraged moves that led to a loss. This resulted in what we can call an “RL policy”. You can think of this as training from first principles - the primary aim is no longer to imitate humans. The aim, instead, is to win! As it should be. An interesting consequence of this binary notion of wins and losses is that AlphaGo focuses on winning, with margin of victory not being much of a factor. It is often seen to start playing defensively once it gains a large enough lead, so as to ensure victory even if territory is lost.

The reason for Stage 1 of this training pipeline is that deep reinforcement learning can be very sensitive. It’s hard to get it working even on relatively simple problems, and difficult to understand why it doesn’t work when it fails. Stage 1 thus gives us a good launching pad to start from. It would be cool if we could start from Stage 2 directly though. That would mean no human professional play was involved in the training process… but more on that later.

Now, that wraps up the policy network. On to the value network. The training for the value network was relatively straightforward. The games that AlphaGo played against itself in stage 2 of the policy network training were recorded, and used to carry out supervised learning to predict game outcomes. So, the training data, essentially consists of (board position, eventual victory or defeat) pairs, and the network learns to map a board position to a probability of victory for either side. Neat!

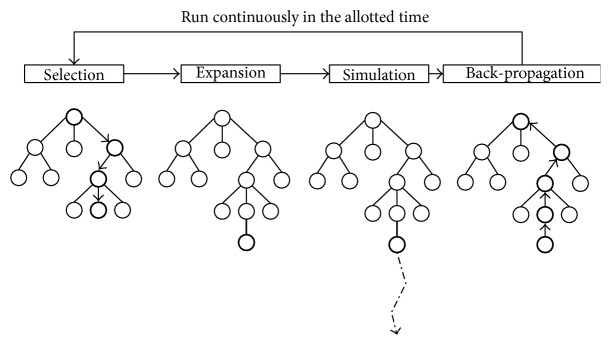

Let’s move on to the component of AlphaGo that most older Go systems use - Monte Carlo Tree Search. The idea is to run a bunch of simulations from the current state of the board to see which moves result in the most wins. At any stage of the game, there are two types of board states - those that we’ve already seen in past simulations, and those that we haven’t. With this in mind, MCTS has 4 stages:

- Selection: From the current board state, we keeping moving forward as long as we’ve seen the states in previous simulations. The choice of move is dependent on the win/loss statistics for the moves we’ve seen. Essentially we want to pick moves that have resulted in wins most often, but also want to give a chance to moves that we haven’t seen too many times.

- Expansion: We keep doing this until we reach a state where the next moves have not been seen before in any simulation. We choose one of these next moves to explore further.

- Simulation: We run a simulation till the end of the game from this move, by guessing what each player would do. In traditional MCTS, it is common for these guesses to just be randomly chosen from the set of all legal moves!

- Backpropagation: Once we reach the end of the game, we go back and update each of the states that we visited along the way with the information of whether the move eventually led to a win or a loss. These statistics can then be used in the “selection” stage in the future!

We keep doing these 4 steps a number of times, updating information after each one, and in the end we simply choose the move that was visited in most simulations! A little bit involved, but as I said before, the key takeaway is simply that we run simulations to see which moves lead to wins most often. You can check out this post if you want more details about MCTS.

While MCTS is a cool idea, it’s been around for a while. What AlphaGo managed to do successfully was combine MCTS with the RL policy, rollout policy and value network that we talked about earlier. The RL policy comes in during expansion, where instead of looking at all the possible legal moves, we focus just on the legal moves that are most “promising”. So we no longer need to get statistics for every possible move - we just need the win/loss statistics for these promising moves, which reduces the number of simulations we have to go through.

The rollout policy and value network come in at the simulation stage. Instead of choosing legal moves randomly to reach the end of the game, we can use the rollout policy. It is computationally cheap, and while it’s not as good as the RL policy, it is significantly better at predicting probable moves than a random policy. Finally, we can use the value network directly from the current position to estimate the probability of winning without actually running the simulation at all! So by combining the game win predictions of the rollout policy with that of the value network, we get a very good estimate to be used in the MCTS process. In fact, DeepMind was able to get excellent performance and beat existing Go programs by using the value network alone, eliminating the need for simulations that go till the end of the game!

tl;dr - AlphaGo uses an RL policy network to reduce the “breadth” of the search tree (by cutting down the list of all possible moves to just the list of promising moves). It then uses a value network to reduce the “depth” of the search tree (by estimating the value of the current game state without simulating till the end of the game). These two key ideas combined with MCTS helped to overcome the immense state space complexity of Go, allowing DeepMind to compete with and beat the best human players in the world.

AlphaGo Zero

About 1.5 years after beating Lee Sedol, in October 2017, DeepMind published a new paper in Nature about their latest breakthrough: AlphaGo Zero. If AlphaGo was all about technical ingenuity, AlphaGo Zero was a feat of technical elegance.

If you read the DeepMind paper or any of the articles about AlphaGo Zero, one phrase keeps jumping out at you - “tabula rasa”. The phrase is Latin, and translates to “blank slate”. It is derived from the nature vs nurture debate in psychology and philosophy, with tabula rasa being the nurture side. You are born as a blank slate, and what you grow to be is dependent entirely on your experiences and the environment you are exposed to.

The relevance of that phrase in this context is related to what we talked about in the previous section, about how AlphaGo had to first be “pre-trained” by learning to predict human moves, after which it was trained from first principles. So the algorithm goes into the actual training process - the RL part - having gained some notion of what constitutes a good move (at least according to human players). AlphaGo Zero, on the other hand, starts directly from the RL part by playing against itself millions of times - with no human knowledge as a starting point! So essentially, it starts as a blank slate, and whatever skills it picks up are learnt purely from experience.

There were some important tricks that DeepMind used to get AlphaGo Zero working. One, was that they combined the “policy” and “value” network into a single network. So the unified network looks at the current board state, and predicts both potential next moves and the value of the game. Intuitively, the insights we use to narrow down good next moves and those we use to predict “goodness” of a state both stem from some fundamental understanding of what the current state “means”. Combining these networks means that the single network is forced to gain this fundamental understanding, which it then applies in 2 different ways. This sort of idea is becoming increasingly popular in the ML community, and is commonly called multi-task learning - use the same model in different but related applications so that it can learn the fundamental commonalities between the two applications.

The second important modification that DeepMind used, was a better utilization of the MCTS we talked about earlier. In AlphaGo, the training phase only involved learning the different networks, and MCTS was used in the final gameplay stage alone. What DeepMind realized is that the predictions of MCTS (with the simulations suggesting good moves to play and also evaluating the value of the game) are better than the raw network predictions - naturally, this is the reason that MCTS is used instead of using the networks directly. But what this meant was the predictions of MCTS could be used as “ground truth” labels that could be used to train the unified policy+value network in a supervised manner! So in a sense, the key aspect of AlphaGo Zero is more about supervised learning using MCTS than it is about RL.

Finally, the actual network structure was revamped using a relatively new network architecture design called a Residual Network (ResNet). Additionally, there were a couple of other simplifications made. AlphaGo had used a small number of hand-crafted features representing the game state (say, something like total territory currently controlled by black and white pieces) which were decided by human experts. These were removed in AlphaGo Zero. The fast “rollouts” from earlier (where the game was simulated upto the very end) were also removed and replaced purely with the predictions of the value network.

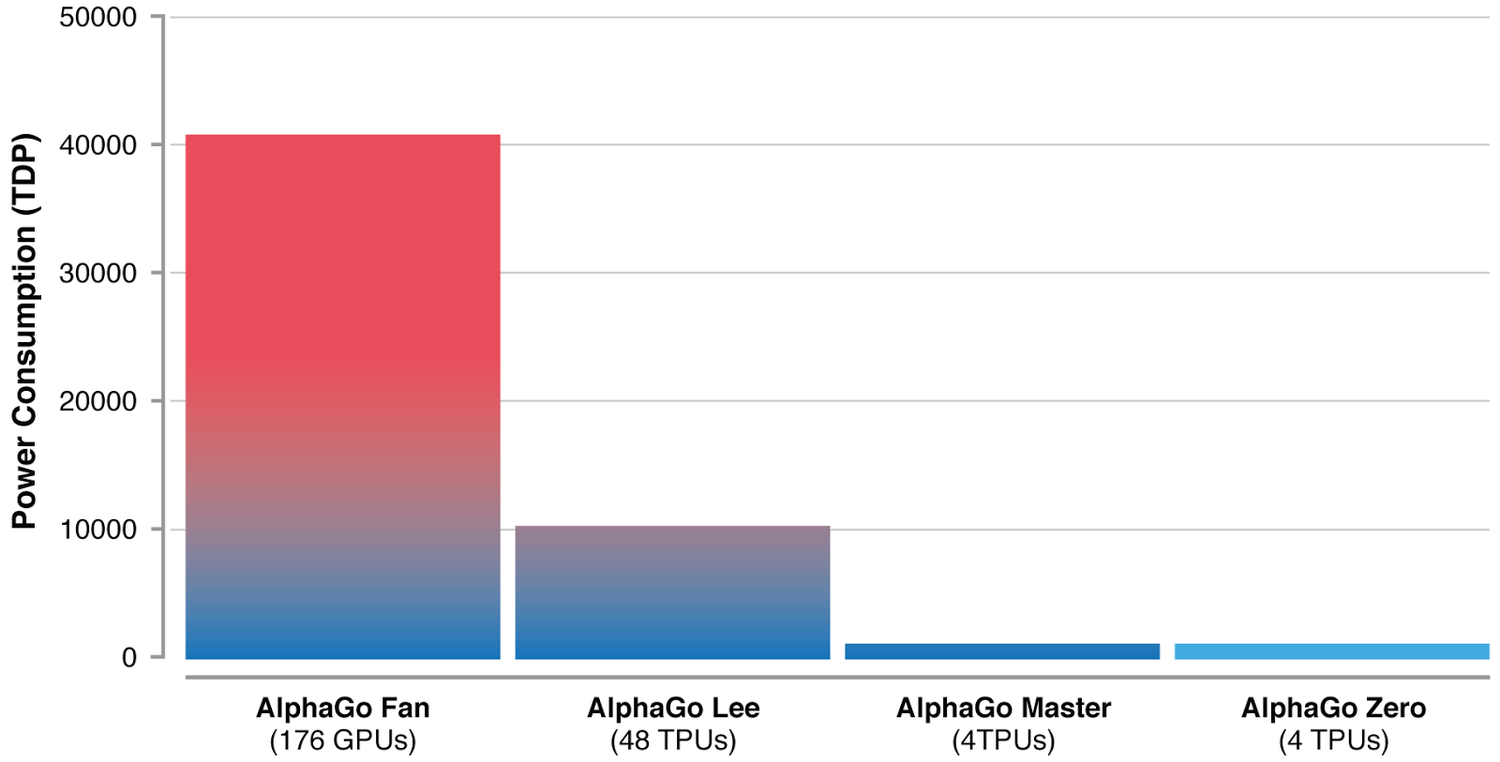

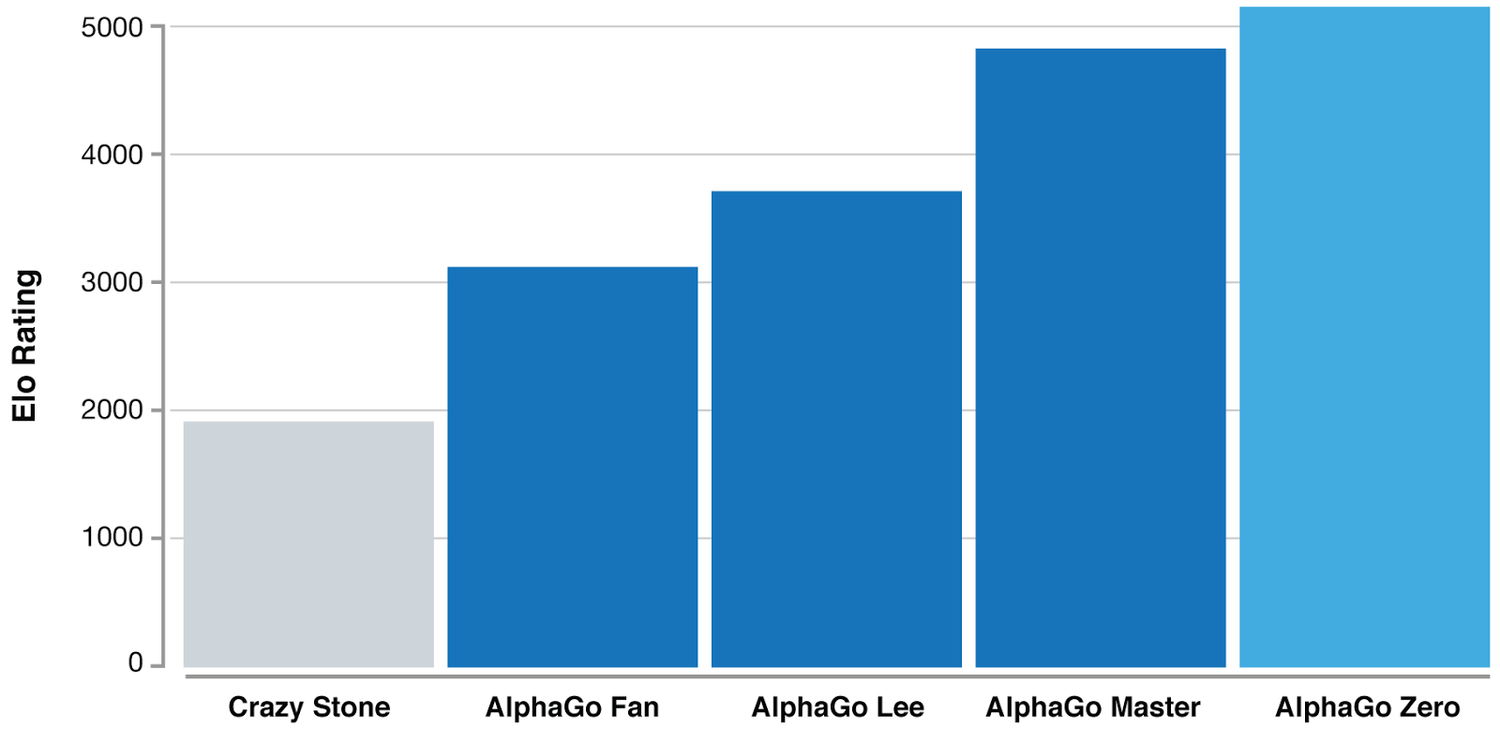

The result of all these changes is a stunning victory of algorithms over computational power, represented best by these two graphs from DeepMind’s blog post:

It took just 3 days of training for AlphaGo Zero to surpass the version that defeated Lee Sedol. In 40 days, it had become the best Go AI (and quite possibly the best Go player) ever. The biggest takeaway - all of this was done without any human supervision or suggestions regarding how Go should be played. The algorithm learnt to do this, from scratch, just by playing against itself. Tabula Rasa.

AlphaZero

AlphaZero, at its core, is simply a generalization of AlphaGo Zero to games other than Go - specifically, chess and shogi (the Japanese version of chess). Go has a lot of useful properties which aren’t possessed by chess or shogi, that make it amenable to the networks used in AlphaGo. Additionally, chess and shogi allow for draws, which is not true of Go. So DeepMind took the core ideas from AlphaGo Zero and, applied the same training procedure to chess and shogi, showing that with just a few hours of training, they could beat the best computer algorithms in the world (Stockfish for chess and Elmo for shogi). Once again, the training involved no supervision based on human games, and AlphaZero learnt to play these games from its own self-play, as opposed to Stockfish and Elmo which employ specialized algorithms and domain-specific human knowledge.

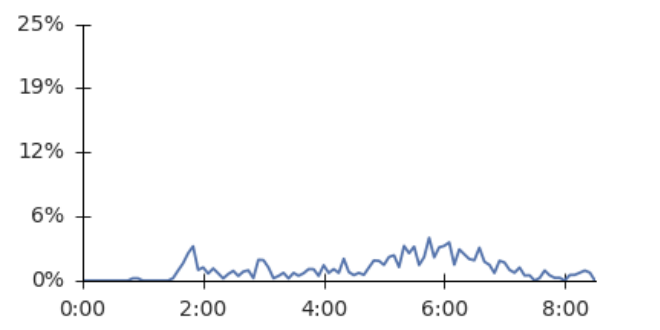

DeepMind does an interesting analysis of AlphaZero’s learning process, where they graph the frequency of popular openings and endgames with learning time. For example, this graph shows the frequency with which AlphaZero plays “The Sicilian Defense” over training:

Initially, as AlphaZero ramps up to what could be called a human performance level, the frequency of these moves goes up. It’s pretty encouraging to see that an algorithm that is designed to learn from first principles (doing whatever it takes to win the game) arrives at the same conclusions we do. What is more interesting to see is that as training continues further, the frequency of these moves goes back down! AlphaZero seems to have moved past the realm of human performance to reach new paradigms of chess play that we’re just beginning to understand.

When Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov in 1997, it led to a drastic shift in the way humans play chess. If an algorithm could beat the best player in the world, then emulating the ideas and moves of that algorithm would improve our own play, right? It is now common to look at what Stockfish predicts to be the best move from a particular situation, and analyze and understand and emulate its gameplay. AlphaZero could represent a whole new shift in our understanding of chess, in the same way. For instance, have a look at this video, where AlphaZero backs Stockfish into a corner, into what is called a “zugzwang” - a position from which any move that Stockfish makes would lead it to a worse position. The sequence of moves that lead AlphaZero there include some which would boggle the minds of our greatest chess players - that’s just not the way we play chess! But it seems to lead to a stronger game nevertheless, and so there’s a lot for us to learn from AlphaZero.

Implications

All of this is very cool stuff, but it’s natural to ask what the real-world implications of these breakthroughs are. The most important one is the fact that it is possible to get world-class performance on a task with zero human supervision. Given a particular task, if we can define its states, actions and rewards in the right way, it should be possible to apply the core ideas from AlphaGo Zero to learn to perform the task without any additional human information. The potential of this idea is mind-boggling.

One simple example - protein folding. Drug discovery, the process of creating new drugs for specific use cases, is fundamentally difficult because it’s hard to “simulate” how a new drug will function without actually testing it out. One reason for this is that even if we have the 2-D chemical structure of a new drug, we’re not good at predicting how the atoms in the drug will align themselves in a 3-D space. For instance, sickle cell anemia is caused because a small change in the 2-D structure of haemoglobin changes its 3-D structure to the eponymous sickle shape. Predicting 3-D structure from 2-D formulae is thus a huge barrier to effective drug discovery and medical research in general. If we can formulate this task in the right way, maybe it can be solved by an RL algorithm, without even feeding it our existing knowledge about protein folding!

Deep RL is still very much a nascent field, and is notorious for being difficult to tune and get working. However, some of the successes in the field in the last few years have paved the way for some potentially incredible applications in the near future. It’ll be great to see the breakthroughs that DeepMind and the RL community come up with next!